MIGRANTS KNOW YOUR RIGHTS –

FACING IMMIGRATION ARREST,

DETENTION, AND DEPORTATION

February 2021

International Human Rights Program, University of Toronto

Butterfly (Asian and Migrant Sex Workers Support Network)

Immigration Legal Committee (No One Is Illegal Toronto)

Funding generously provided by the Law Foundation of Ontario; the authors

are solely responsible for all content.

This guide may be cited as follows: International Human Rights Program,

Butterfly & No One Is Illegal Toronto, “Migrants Know Your Rights – Facing

Immigration Arrest, Detention, and Deportation” (2021).

The guide was developed through close consultation with community

partners and drafted by Liam Turnbull, Vincent Wong, Marissa Hum, Elene

Lam, and Macdonald Scott.

Editors: Ashley Major and Prasanna Balasundaram

Graphic design: Lorraine Chuen

Note: This guide provides general legal information and does not provide

legal advice. Please talk to a lawyer or advocate if legal help is required.

Licensed under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 (Attribution-ShareAlike

Licence)

The Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 license under which this

report is licensed lets you freely copy, distribute, remix, transform, and build

on it, as long as you:

● Give appropriate credit;

● Indicate whether you made changes; and

● Use and link to the same CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION 5

1.1 Disclaimer 5

1.2 Purpose of the guide 6

1.3 Importance of understanding arrest, detention, and deportation systems 7

1.4 Limits of relying on legal rights 7

1.5 What is the CBSA? 7

1.6 What is the IRB? 8

2. WHO IS AT RISK OF IMMIGRATION ARREST, DETENTION, AND DEPORTATION? 10

2.1 Falling out of status 10

2.2 Immigration arrests with and without a warrant 13

2.3 Permanent residents 15

2.4 Practical tips 16

3. HOW WILL I KNOW IF I AM FACING DEPORTATION AND HOW CAN I REGULARIZE

STATUS? 18

3.1 How to check status 18

3.2 What is a Removal Order? 19

3.3 How to regularize or retain status 20

4. WHAT IS THE DEPORTATION PROCESS AND WHAT SHOULD I DO IF I AM BEING

DEPORTED? 24

4.1 Deportation process flowchart 24

4.2 Safety plan in case of arrest 25

4.3 Reporting to CBSA 26

4.4 Practical tips 28

5. WHAT IF I AM ARRESTED AND PUT IN IMMIGRATION DETENTION? 29

3

5.1 Detention process flowchart 29

5.2 Grounds for immigration detention 30

5.3 Rights when you are arrested and detained 31

5.4 What to expect in detention 32

5.5 Getting out of detention 36

5.6 Practical tips 38

6. WHAT ARE SOME RESOURCES AND SUPPORT THAT I CAN REACH OUT TO? 40

6.1 Legal aid 40

6.2 Migrant support organizations 44

6.3 Further Considerations 46

7. APPENDICES 47

7.1 Safety plan checklist 47

7.2 Summary of practical tips 47

8. GLOSSARY AND KEY TERMS 49

4

1. INTRODUCTION

This guide provides legal information for migrants navigating processes of immigration arrest,

detention, and deportation. It provides general guidance so that you can know your legal rights while

living in Canada and practical tips for engaging with the country’s immigration detention and

deportation processes.

This guide may be helpful for you if any of the following apply:

● You are a service provider offering support or advice to migrant workers;

● You are a temporary resident (e.g. migrant worker, international student, under sponsorship);

● You are a non-citizen with potentially precarious immigration status;

● You are an asylum seeker or failed asylum claimant;

● You are a non-citizen who does not have any status in Canada; or

● You wish to support individuals to whom the above circumstances are applicable.

Other Useful Migrant Legal Rights Guides

● Migrants Know Your Rights! (2012, No One is Illegal Toronto)

● Immigration consequences of criminal dispositions and sentencing (2016,

Community Legal Education Ontario Legal Aid Ontario)

1.1 Disclaimer

This document provides general legal information and does not provide legal advice. Please consult a

lawyer or legal aid clinic for legal advice specific to your situation. Some examples and response data

may have omitted identifying data in order to protect the confidentiality and privacy of those involved.

5

If You Need Legal Representation, You Can Contact...

Legal Aid Ontario

Toll free phone number: 1‑800‑668‑8258

Web: https://www.legalaid.on.ca/more/corporate/contact-legal-aid-ontario

Law Society of Ontario (LSO) Lawyer Referral Service

Phone number: 1-855-947-5255

Web: https://lsrs.lso.ca/lsrs/welcome

For legal aid in other provinces, you can refer to the federal government’s directory:

https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/fund-fina/gov-gouv/aid-aide.html

1.2 Purpose of the guide

This guide builds off of previous ‘Migrants Know Your Rights’ guides

1

to provide updated, current legal

information on the rights of those with precarious immigration status who are or may be at risk of

being caught in the deportation process in Canada.

Specifically, you can find information in this guide on:

● Who is at risk of immigration arrest, detention, and deportation;

● How to know if you are facing deportation and how you can regularize status;

● What the deportation process is and what you should do if you are being deported;

● What to do if you are arrested and put in immigration detention;

● Practical tips to create safety plans and reduce your risk of detention; and

● Additional supports and resources that you can reach out to.

The contents of the guide were developed in consultation with migrant community organizations as

well as affected individuals themselves.

1

For instance, see Immigration Legal Committee’s past “Migrants Know Your Rights!” Guide, available online (PDF) at:

<toronto.nooneisillegal.org/sites/default/files/KYR%20ENGLISH%20PDF%20FINAL_0.pdf> [https://perma.cc/26K4-B5V4]

[Immigration Legal Committee, “Migrants Know Your Rights!”].

6

1.3 Importance of understanding arrest, detention, and deportation systems

You should be aware of how immigration arrests, detentions, and deportations take place, and your

rights in these situations. This will help you to better protect yourself and your loved ones by allowing

you to more easily navigate processes and prepare yourself for risks. You can also learn how to put

appropriate plans in place, gain practical tips that you can use in your day-to-day life, and know what

resources and supports are available should the need arise. If you believe that you are facing

significant risk, please consult a lawyer and get legal advice about your specific situation.

1.4 Limits of relying on legal rights

Knowing one’s legal rights, the state of the laws, and helping others advocate for their rights is

important. However, this does not change the fact that the current legal framework in this country

ensures that individuals with uncertain/precarious immigration status are at constant risk of

immigration arrest, subsequent detention, and potential deportation by immigration authorities – which

in turn serves as a silencing mechanism and a form of political suppression. Migrants are more likely to

face exploitative conditions at work and in their lives more generally. They also have difficulties

accessing employment, education, and crucial health and social services. Permanent resident status is

also increasingly difficult to obtain due to policies put forward by successive Canadian governments.

These realities underscore the importance of going beyond the current state of the law and organizing,

mobilizing, creating personal or community safety plans, resisting immigration detention and

deportation, and creating a political and legal system where all migrants have their basic rights and

human dignity protected and respected. Laws should not be conflated with justice, nor should law be

the only site for struggle for social change.

1.5 What is the CBSA?

The Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) is the government agency that is in charge of enforcing

immigration laws (such as the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act – “IRPA” – and the Immigration

and Refugee Protection Regulations – “IRPR”).

2

CBSA officers have the power to arrest and detain

individuals who are in violation of immigration laws, including if they are in Canada without valid

status. They are also able to issue arrest warrants and deportation orders for your removal from

Canada. Although CBSA officers have broad powers and discretion, they are not police officers – they

have different legal powers and do not enforce criminal laws.

3

CBSA is different from Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). The IRCC is a civilian

body that administers the immigration system and makes immigration decisions but does not enforce

the laws. You may have interactions with both IRCC and CBSA at the same time.

3

See Section 2.2 and Section 4.3 of this guide for further information on CBSA’s legal powers.

2

See Government of Canada, “Home - Canadian Border Services Agency” (Date modified: 01 May 2020), online:

<www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/menu-eng.html> [https://perma.cc/JKZ3-JPFE]; Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c. 27

[IRPA]; Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (Consolidation), SOR/2002-227, at s 179-182 [IRPR].

7

1.6 What is the IRB?

The Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) is Canada’s largest administrative decision-making tribunal

and the primary body that decides on issues concerning immigration and refugee law.

4

Divisions of the Immigration and Refugee Board (“IRB”):

● Immigration Division

● Immigration Appeal Division

● Refugee Protection Division

● Refugee Appeal Division

FAQ: https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/faq/Pages/index.aspx

The IRB is further broken down into smaller divisions that manage specific areas of immigration and

refugee law. Each division is obligated to provide interpreters for all proceedings.

5

These divisions are

the Immigration Division, Refugee Protection Division, Immigration Appeal Division, and the Refugee

Appeal Division. The following is a description of each Division and what it is responsible for:

Immigration Division:

● Hears detention reviews;

● Holds cancellation of immigration status hearings

6

;

● Holds admissibility hearings

7

;

● Procedures can sometimes be very loose and informal;

● It’s a good idea to have legal counsel, or if not, have a trusted contact to attend proceedings

with you.

8

8

If these individual representatives charge you money, they must be either a member of the law society of the relevant

province or territory, a member of the Immigration Consultants of Canada Regulatory Council, or (in Quebec only) a Notary

Public. Legal aid can fund a lawyer in some provinces and territories for these hearings (this means the lawyer would be free;

legal aid will also not share your information with immigration authorities).

7

See Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, “Immigration and Refugee Board at a glance” (Date modified: 17 June

2019), online: <irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/information-sheets/Pages/irbGlance.aspx> [https://perma.cc/2TX2-L9HL] [Immigration and

Refugee Board of Canada].

6

IRPA, supra note 2, at ss 33-43.

5

See Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, “Interpreter Handbook” (October 2017), online (PDF):

<humaneimmigration.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/05-Interpreter-Handbook-Immigration-and-Refugee-Board-of-Cana

da.pdf> [https://perma.cc/Q98S-D9YH] at section 2.1.

4

See Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, “Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada” (Date modified: 15 May 2020)

online: <irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/Pages/index.aspx> [https://perma.cc/6NN5-TSW8]. The powers of the IRB are set out in sections

151 – 186 of the IRPA, supra note 2.

8

Immigration Appeal Division:

9

● Hears appeals from the Immigration Division;

● Hears spousal sponsorship appeals;

● More formal tribunal than the Immigration Division – has more strict procedural rules.

Refugee Protection Division:

10

● Hears refugee and protected person claims;

● Can reject claims for refugee protection or grant refugee status;

● Cessation and vacation proceedings where you can lose your protected person status.

Refugee Appeal Division:

11

● Hears appeals from the Refugee Protection Division;

● Can reverse or confirm the decision of the Refugee Protection Division or send the case back for

a new decision.

11

See Government of Canada, “Refugee Appeal Division” (Date modified: 17 May 2019), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/canada-role/refugee-appeal-division.html>

[https://perma.cc/3ZV6-ACXE]; Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, supra note 7; see also Government of Canada,

“Refugee Appeal Division Rules” (Date modified: 28 May 2020), online:

<https://www.laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2012-257/FullText.html> [https://perma.cc/5CPC-QEPK].

10

See Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, supra note 7; see also Government of Canada, “Refugee Protection Division

Rules” (Date modified: 28 May 2020), online: <https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/sor-2012-256/FullText.html>

[https://perma.cc/S5RJ-HQ7K].

9

See Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, “Immigration Appeals” (Date modified: 05 July 2018), online:

<irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/information-sheets/Pages/FactIadSai.aspx> [https://perma.cc/SFQ6-9Q3B]; see also Immigration and

Refugee Board of Canada, supra note 7.

9

2. WHO IS AT RISK OF

IMMIGRATION ARREST, DETENTION,

AND DEPORTATION?

If you fall out of status and/or are deemed ‘inadmissible’ under IRPA, you can be subjected to

immigration arrest, detention, and eventually deportation.

2.1 Falling out of status

12

These are some of the most common ways that you may fall out of status or otherwise become

inadmissible in the eyes of Canadian immigration:

You can fall out of status / become inadmissible due to reasons such as:

● Overstaying your visa

● Voluntary repatriation

● Losing your refugee application and

appeal

● Criminal convictions

● Lacking a temporary visa

Overstaying your visa:

13

If you are not from a visa-exempt country and overstay your visa, you could lose your status and be put

in immigration detention. It is important to check your visa dates closely and ensure you apply for

extensions early. Local CBSA officers have ways of checking whether you overstayed your visa and

may arrest and detain you if they reasonably suspect that you are overstaying. They can call CBSA

headquarters to check your ‘global case management file’ in order to confirm your entry and exit dates

to/from Canada and use that information to argue you overstayed.

14

14

For further information on the global case management system, see Government of Canada, “Privacy Impact Assessment

Summary – Global Case Management System (GCMS) - Phase II” (Date modified: 10 February 2012), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/transparency/access-information-privacy/privacy-impa

ct-assessment/global-case-management-system-2.html> [https://perma.cc/JL3T-WKZ8].

13

See IRPA, supra note 2 at s 41 (with regard to the consequences of ‘non-compliance’ of immigration law).

12

Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “Inadmissibility (ENF1)” (04 September 2013),

online: <https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf01-eng.pdf>

[https://perma.cc/3GEW-8A4Q] at 3, 4, 5, 6 [Operation Manual, “ENF1”].

10

If you are from a visa-exempt country, you can only stay for up to six months (unless your passport

stamp or your travel document says differently). Before your time is up, you either need to leave

Canada or renew your visitor status from within Canada.

15

People typically fall out of status this way

by having their applications for extension denied or forgetting to apply before their permit expires.

Technically, you must have at least a temporary resident visa (“TRV”) or a temporary resident permit

(“TRP”) to remain in Canada temporarily (unless you fall into a special exception). A work permit or

study permit is not the same as a TRV or TRP, but typically are issued together. It is possible in certain

scenarios to have a work/study permit without underlying status and be allowed to remain, but these

situations are rare.

16

The main takeaway is that if you have a work/study permit despite not having a

valid TRV or TRP, you may not be safe from immigration arrest, detention, and deportation.

17

Voluntary Repatriation:

18

If you are granted refugee or protected person status by Canada and you return to your country of

origin, you may risk losing your status (even after you received PR status) if it is determined that you

voluntarily returned there, re-acquired their nationality (for instance, by applying for a passport),

re-established yourself there, or if the reasons for seeking protection originally no longer exist. This is

because Canada believes a “genuine” refugee would not be able to return to the country where they

fear persecution or danger, so returning to that country means you no longer need Canada’s

protection.

19

The consequences of such a determination can be severe, including being found

inadmissible and being deported.

Criminal Inadmissibility:

20

If you are convicted of a crime, you could lose your immigration status. Whether you lose your status

depends on how “serious” the crime is, the specific crime committed, and the type of status you

possess (e.g. temporary status, permanent resident status). For instance, someone with permanent

20

See IRPA, supra note 2 at ss 33-43. For a summary of the criminal inadmissibility process, see Canadian Council for

Refugees, “Permanent residents and criminal inadmissibility” (July 2018), online:

<https://ccrweb.ca/en/permanent-residents-and-criminal-inadmissibility>.

19

See United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Handbook – Voluntary Repatriation: International Protection”

(Geneva: 1996), online:

<www.unhcr.org/publications/legal/3bfe68d32/handbook-voluntary-repatriation-international-protection.html>

[https://perma.cc/5BMX-E6T4].

18

See IRPA, supra note 2 at s 108; Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act, SC 2012, c 17, ss 18-19 (2012

amendments).

17

See Government of Canada, “Temporary resident permits: Work and study permits” (Date modified: 17 September 2015),

online:

<https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/operational-bulletins-manuals/t

emporary-residents/permits/work-study-permits.html> [https://perma.cc/2Z2G-LN9D].

16

For instance, CBSA may in some cases not start deportation proceedings if you have a strong claim for being granted PR

status on Humanitarian and Compassionate grounds. Depending on your specific situation, the Minister of Immigration,

Refugees and Citizenship may grant you permanent resident status on ‘Humanitarian and Compassionate grounds’ if you

would not otherwise qualify for permanent resident status. For more information, see Section 3.3 of this guide (“3.3 How to

Get Status”).

15

For further information on visitor visas, see Section 3.3 of this guide (“3.3 How to Get Status”).

11

resident status could lose that status if they receive a prison sentence of over 6 months for a given

crime, or if the crime itself carries a maximum prison sentence of 10 (or more) years.

21

On the other

hand, someone without permanent resident status could lose their immigration status if they are

convicted of an ‘indictable’/‘hybrid’ offence

22

or two different offences that arose from separate events,

even if they are minor.

23

‘Serious criminality’/‘criminality’ is determined based on the nature of the offence and the type of

punishment for the crime (e.g. the length of the prison sentence).

24

Individuals that are found criminally

inadmissible and deported will not be allowed to return to Canada unless they have an ‘Authorization

to Return to Canada’ (“ARC”).

25

Whether you are a permanent resident or a foreign national, you should always consult with counsel

about immigration consequences to criminal pleas or convictions.

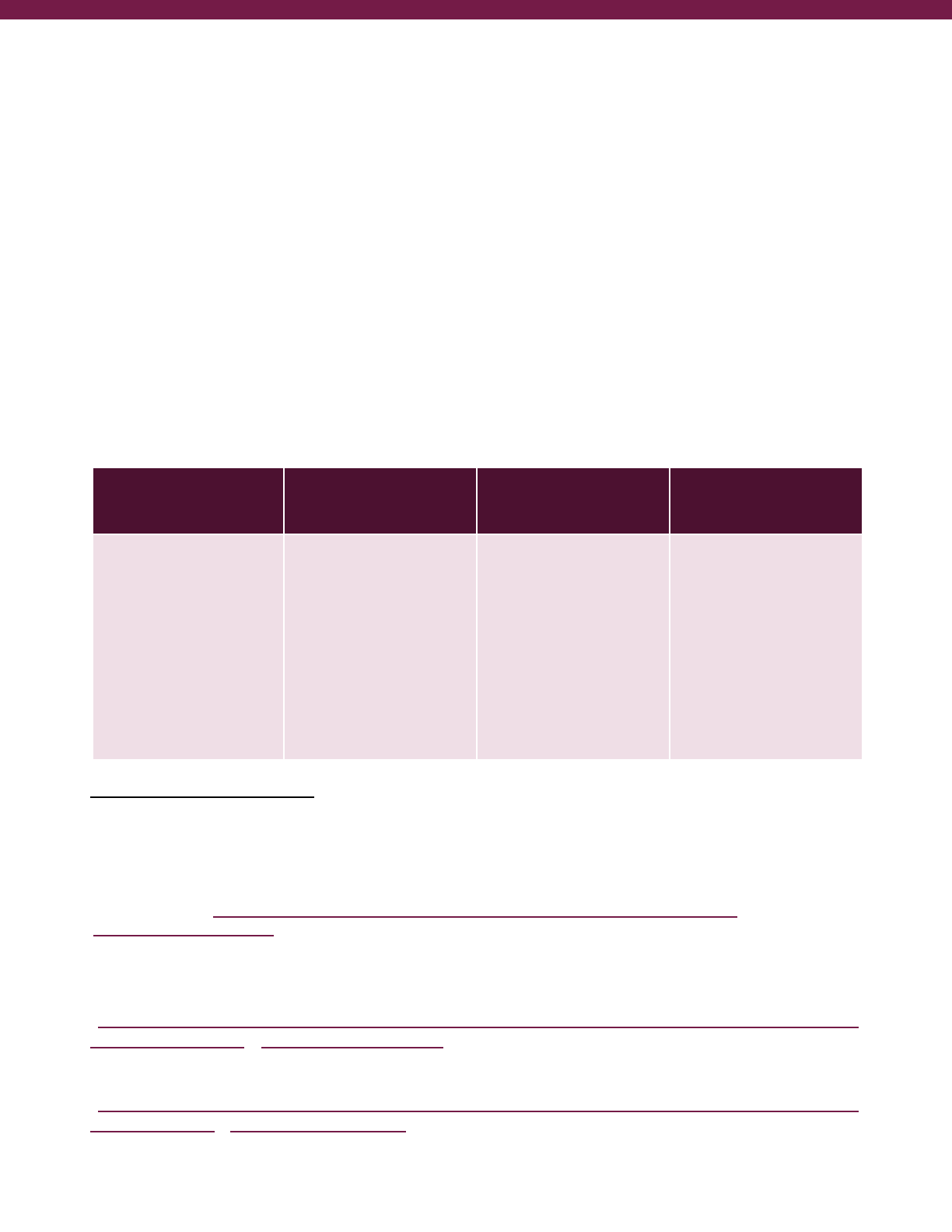

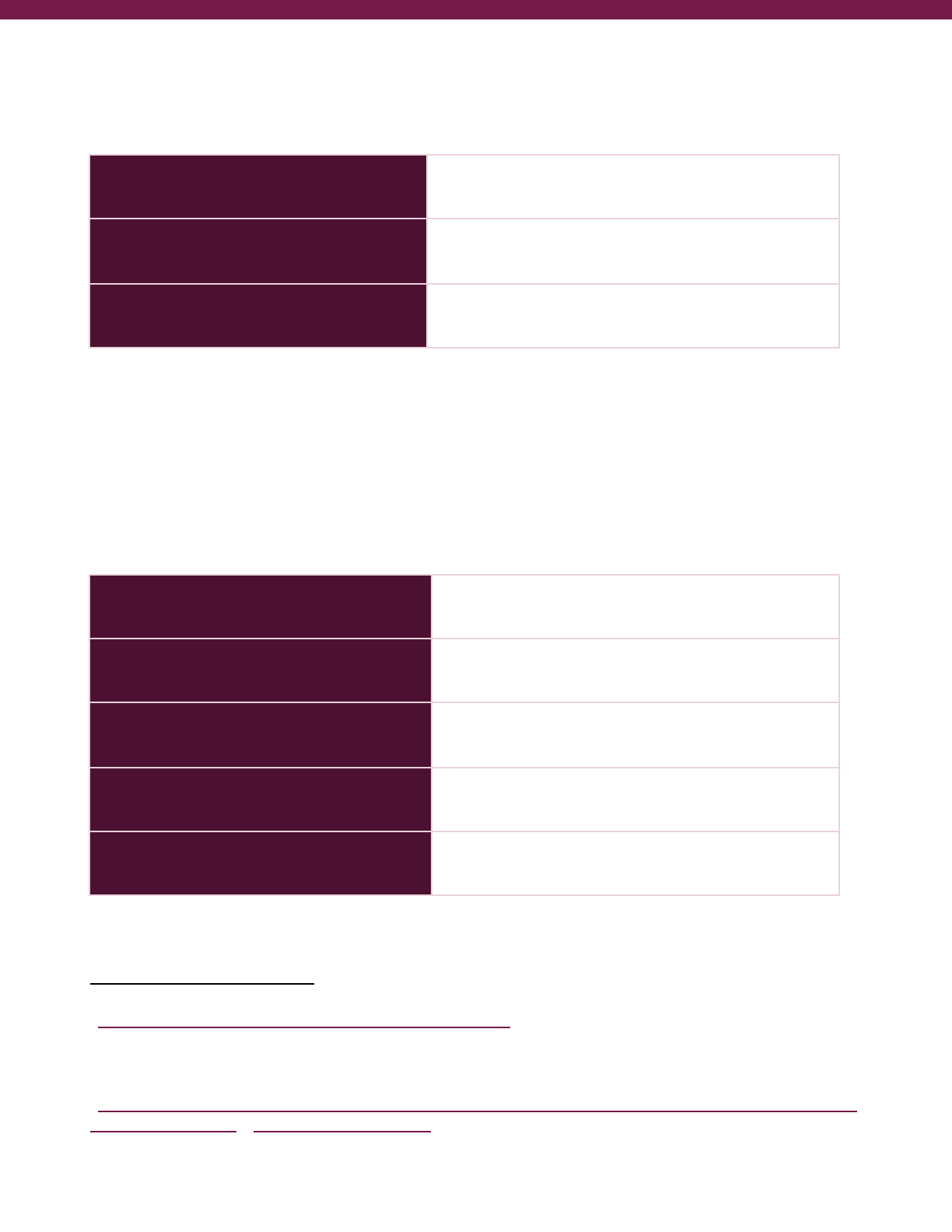

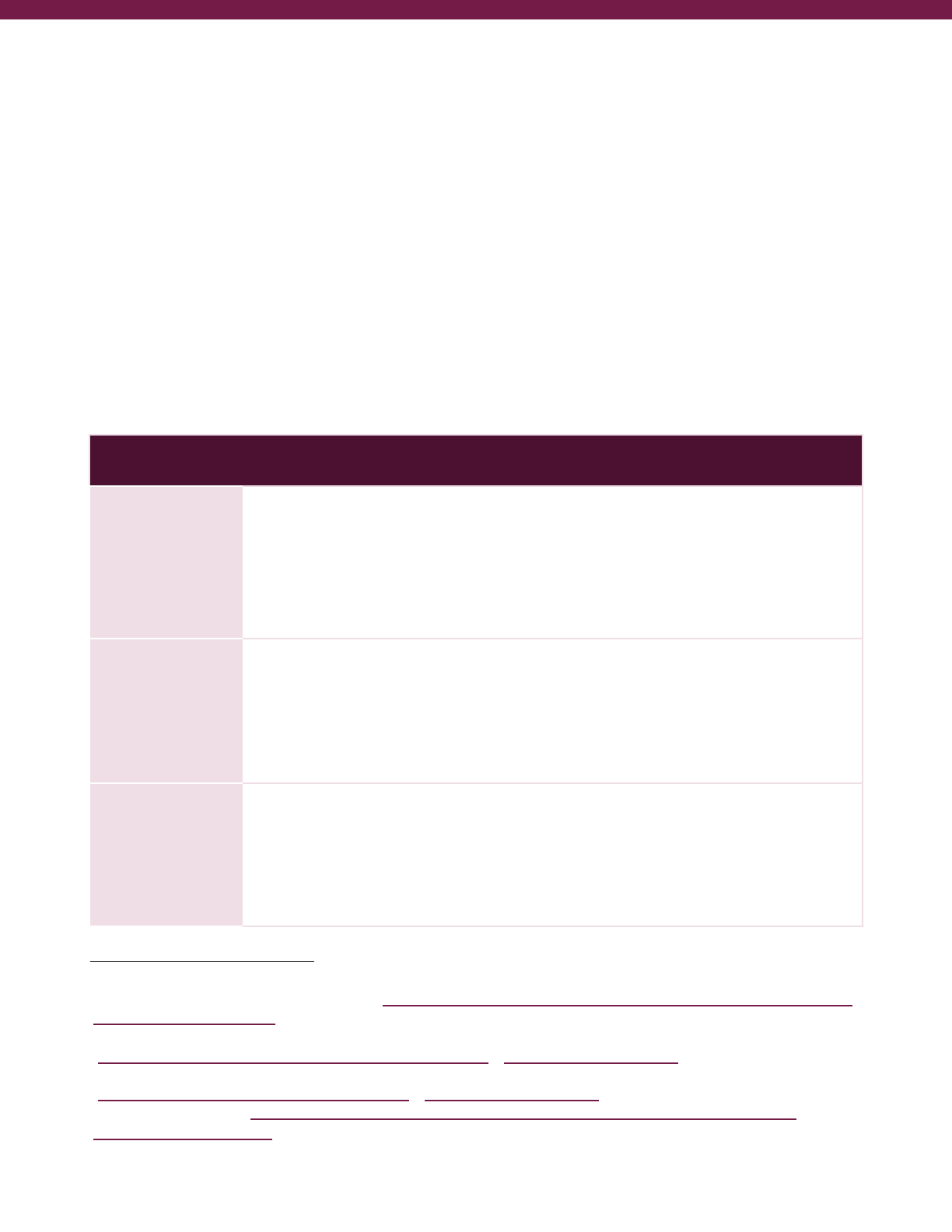

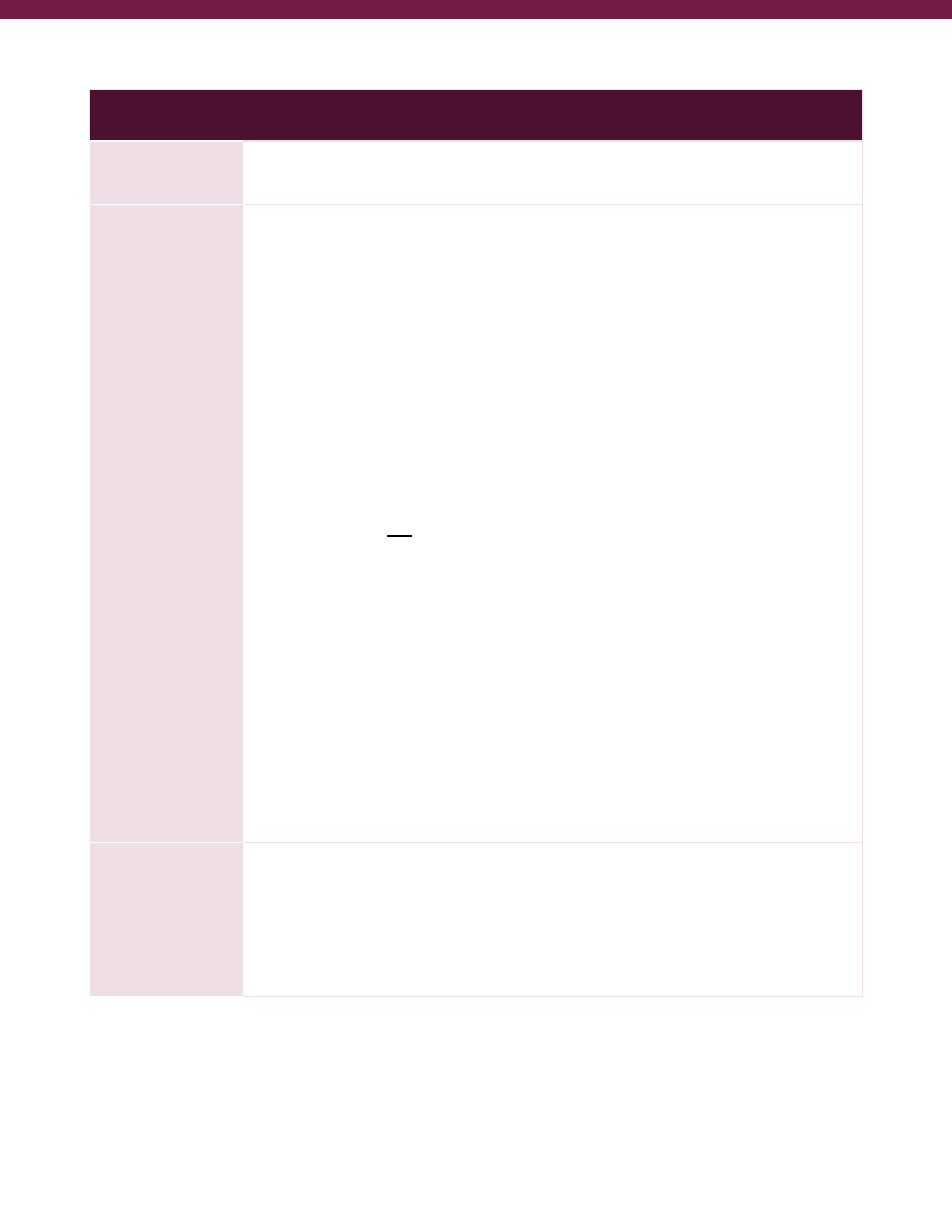

The following table summarizes some of the potential consequences of being convicted for a criminal

offence for individuals with different statuses:

CANADIAN CITIZENSHIP

PERMANENT

RESIDENCE (PR)

TEMPORARY

RESIDENCE (TR)

NON-STATUS

● Arrest, detention,

prosecution

● Imprisonment, fines

● Criminal record

● Arrest, detention,

prosecution

● Imprisonment, fines

● Criminal record

● Depending on

severity, may lose

PR status and be

deported

● Arrest, detention,

prosecution

● Imprisonment, fines

● Criminal record

● Depending on

severity, may lose

TR status and be

deported (lower

threshold than PR)

● Arrest, detention,

prosecution

● Imprisonment, fines

● Criminal record

● Most likely

deportation, even if

not convicted

● Likely to be turned

over to CBSA for

processing

25

For more information on the ‘Authorization to Return to Canada’ process, see Government of Canada, “Authorization to

return to Canada” (Date modified: 27 March 2020), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/inadmissibility/reasons/authorization

-return-canada.html> [https://perma.cc/6QFD-ULY6] [Government of Canada, “Authorization to return to Canada”].

24

See Government of Canada, “Assessing inadmissibility due to serious criminality following Tran v. Canada” (Date modified:

14 November 2019), online:

<www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/operational-bulletins-manuals/standar

d-requirements/tran.html> [https://perma.cc/N73U-JWNP].

23

See IRPA, supra note 2 at s 36(2).

22

In Canada, there are ‘indictable’ offences and ‘summary’ offences. Summary offences are less serious and often carry

shorter prison sentences and fines. Indictable offences are more serious and carry heavier punishments, including mandatory

minimum prison sentences in some cases. ‘Hybrid’ offences will be treated as indictable offences for immigration purposes –

see IRPA, supra note 2 at s 36(3)(a). For more information, see Department of Justice, “Criminal offences” (Date modified: 24

July 2015), online: <www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/victims-victimes/court-tribunaux/offences-infractions.html>

[https://perma.cc/9MGT-XQ3K].

21

Ibid at s 36(1).

12

2.2 Immigration arrests with and without a warrant

A CBSA officer can issue an arrest for someone who is believed to be ‘inadmissible’ or lack status

under IRPA.

26

CBSA officials are only allowed to arrest individuals for immigration reasons. Police

officers, however, can also arrest you for immigration reasons if there is an arrest warrant for you , or

the police have other non-immigration grounds to arrest you.

27

In reality, if police officers suspect you do not have proper immigration status, have broken the

conditions of your visitor visa, work permit or study permit, or violated other immigration rules, they

may try to detain you, call CBSA, and turn you over to them.

28

Many immigration-related arrests in

Canada are made by local police. Other government officials, such as local municipal by-law officers,

generally do not have any power to arrest you.

29

Police and other law enforcement often take

advantage of the grey zone in which there are no legal grounds to detain, until CBSA shows up.

When a warrant for arrest is needed:

Depending on the situation, an immigration arrest could take place with or without a warrant.

30

A warrant is needed to arrest you when:

● You are within the privacy of your own home

31

;

● You are a foreign national, but you are a ‘protected person’ under IRPA

32

;

● You are a permanent resident (although CBSA does not need a warrant to detain at a port of

entry)

33

;

33

See Bedada v. Canada (Solicitor General), 2007 FC 121 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/1qflp>; see also X (Re), 2014 CanLII

94241 (CA IRB), <http://canlii.ca/t/gktb0>; IRPA, supra note 2, at s 55; Maynard, supra note 32 at s 2.

32

IRPA, supra note 2, at s 55(2); Gordon Maynard, “Arrest and Detention” (May 2013), online:

<http://www.cba.org/CBA/cle/PDF/IMM13_paper_maynard.pdf> [https://perma.cc/4NQS-VST8] at s 2 [Maynard].

31

See Community Legal Education Ontario (CLEO), “In what urgent situations can the police enter my home?” (October

2019), online: <https://www.cleo.on.ca/en/publications/polpower/what-urgent-situations-can-police-enter-my-home>

[https://perma.cc/L5S2-LH32]; See also Immigration Legal Committee, “Migrants Know Your Rights!”, supra note 1 at 3.

30

See Citizenship and Immigration Canada, “ENF 7 Investigations and Arrests” (May 2003) at 34, 38, 39 [“ENF 7”].

29

See Butterfly, “Upholding and promoting human rights, justice and access for migrant sex workers - Part 1: Guide for

Service Providers” (October 2017), online:

<https://576a91ec-4a76-459b-8d05-4ebbf42a0a7e.filesusr.com/ugd/5bd754_3284af1908704da0935a4cf60e66abf3.pdf>

[https://perma.cc/WPM4-UNV4] at 22 [Butterfly, “Upholding and promoting human rights- Part 1”].

28

See Abigail Deshman, “To Serve Some and Protect Fewer: The Toronto Police Services' Policy on Non-Status Victims and

Witnesses of Crimes” (2009) 22:8 J L & Soc Pol’y 209 at 219-220.

27

See Butterfly, “Who is who: Identifying law enforcers” (July 2017), online:

<https://576a91ec-4a76-459b-8d05-4ebbf42a0a7e.filesusr.com/ugd/5bd754_748f9f3d7c9a4139b999f5b4a26b9f7a.pdf>

[https://perma.cc/ZAS3-SUK5] at 2 [Butterfly, “Who is who”].

26

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 55.

13

● You fail to report to the CBSA

34

; or

● You fail to attend admissibility hearings

35

.

You can be arrested by CBSA without a warrant when:

● You are without valid immigration status

36

;

● You are working in Canada without a valid work permit

37

;

● CBSA officials/police have reasonable grounds to believe that you lack status, or are

inadmissible and pose a danger to the Canadian public under IRPA

38

;

● If you are a temporary resident or student and CBSA decides you are unlikely to show up for

examinations or hearings

39

, you pose a danger to the public, or they believe they can’t identify

you

40

;

● You incorrectly identify yourself to officials, and/or your identity cannot be established

41

; or

● You are charged with a criminal offence, or the police have reasonable grounds to believe you

committed (or are about to commit) a serious crime

42

.

42

See generally: Steps to Justice, “The police have arrested me without a warrant. What should I do?” (02 November 2018),

online: <https://stepstojustice.ca/questions/criminal-law/police-have-arrested-me-without-warrant-what-should-i-do>

[https://perma.cc/2ZTK-WD3Y]; See also Butterfly, “Guide for Service Providers: ‘A Pathway to End Violence Against Migrant

Sex Workers: Access, Safety, Dignity and Justice’” (2020), online:

<https://576a91ec-4a76-459b-8d05-4ebbf42a0a7e.filesusr.com/ugd/5bd754_d680b25295cb40bdbbcc03f34a88c267.pdf

> [https://perma.cc/GZU2-3ENM] at 35 [Butterfly, “Pathway to End Violence”].

41

See Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Mwamba, 2003 FC 1042 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/1fzn0> at para

14; see also R. c. Patel, 2018 QCCQ 7262 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/hvk62>; See also Immigration Legal Committee,

“Migrants Know Your Rights!”, supra note 1 at 5.

40

Steps to Justice, “I am not a Canadian citizen. Can immigration authorities detain me?” (15 May 2019), online:

<https://stepstojustice.ca/questions/refugee-law/i-am-not-canadian-citizen-can-immigration-authorities-detain-me>

[https://perma.cc/288A-CLYL].

39

See Sibomana v. Canada, 2019 FC 945 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/j1z1r> at para 37; Larson v. Canada (Minister of Public

Safety and Emergency Preparedness), 2005 FC 986 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/1l7d2> at para 18.

38

Ibid at 6, see also Canada (Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness) v. Ismail, 2014 FC 390 (CanLII), [2015] 3 FCR 53,

<http://canlii.ca/t/g6mxd> at paras 29 and 45; IRPA, supra note 2 at s 55(2); Ibid at 6.

37

Ibid at 6.

36

Immigration Legal Committee, “Migrants Know Your Rights!” supra note 1 at 5.

35

Ibid. An arrest warrant was eventually issued for Sergey Ivlev since he did not show up for his admissibility hearing.

34

For a discussion of how arrest warrants may be issued for individuals who fail to report to the CBSA, see Ivlev v. Canada

(Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness), 2010 CanLII 38259 (CA IRB), <http://canlii.ca/t/2bk4k>.

14

CBSA’s ‘Reasonable Belief’ That You Violated Immigration Law:

Generally CBSA may only arrest you on immigration grounds if they have a ‘reasonable belief’ that you

violated immigration law or stay conditions.

43

However, as discussed above in Section 1.5, the CBSA

has broad discretionary power to enforce Canada’s immigration laws and it may be difficult to formally

challenge whether an immigration arrest was in fact reasonable.

2.3 Permanent residents

44

Individuals with permanent resident status have greater protection than those with temporary or no

status, but are still at risk of immigration arrest, detention, and deportation in certain cases. They can

be found inadmissible under IRPA for the following reasons:

Reasons that permanent residents can be found inadmissible under IRPA:

● On security grounds

● Due to human/international rights

violations

● Serious criminality

● Organized criminality

● Misrepresentation

There is often no right of appeal on these inadmissibility grounds except for misrepresentation or on

minor criminality grounds where you were not sentenced to 6 months or more of imprisonment.

45

On security grounds:

46

This means you would be inadmissible because your presence in the country is deemed a national

security threat by Canada. Examples of behaviour that affects national security include: acts of

espionage, terrorism, violence that can endanger the public, or being involved in an organization that is

deemed to have engaged in these acts.

46

Ibid at s 34(1).

45

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 64.

44

See Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “Inadmissibility (ENF1)” (04 September

2013), online: <https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf01-eng.pdf>

[https://perma.cc/3GEW-8A4Q] at 3, 4, 5, 6; see also Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

(IRCC), “ENF 23 Loss of permanent resident status” (23 January 2015), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf23-eng.pdf>

[https://perma.cc/MFQ3-LHJL].

43

See Butterfly, “Upholding and promoting human rights, justice and access for migrant sex workers: Part 3 - Legal

information for migrant sex workers” (October 2017), online:

<https://576a91ec-4a76-459b-8d05-4ebbf42a0a7e.filesusr.com/ugd/5bd754_506c23f7470e459f802c842381a1b1eb.pdf

> [https://perma.cc/PQW2-32UM] at 3; Canada (Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness) v. Ismail, 2014 FC 390 (CanLII),

[2015] 3 FCR 53, <http://canlii.ca/t/g6mxd> at para 29, 45; IRPA, supra note 2 at s 55(2); See also Immigration Legal

Committee, “Migrants Know Your Rights!”, supra note 1 at 6.

15

Violation of human/international rights:

47

You could be found inadmissible if you broke international human rights laws through your actions.

This includes very serious crimes such as acts of genocide, war crimes, or crimes against humanity.

Serious criminality:

48

Committing crimes that Canada deems particularly serious in nature could lead to a finding of

inadmissibility. This includes offences committed while in Canada that have a maximum prison

sentence of 10 years or more, convictions that have resulted in a prison sentence of 6 months or more,

and offences committed outside Canada which carry a maximum prison sentence of 10 years or more

(whether in that country or, if the act occurred in Canada, would result in that type of offence which

carries that prison sentence length).

Organized criminality:

49

These include transnational criminal offences like human trafficking, money laundering, the smuggling

of persons/goods, or being involved in an organization that commits these offences

50

.

Misrepresentation:

51

This includes acts where you withhold material facts that are relevant to your status under IRPA,

misrepresenting (directly or indirectly) such facts, or being sponsored by an individual who has

engaged in these acts of misrepresentation.

2.4 Practical tips

52

If you are in a situation where you may be at risk of immigration arrest, detention, or deportation, make

efforts to find a legal representative and/or seek legal advice as soon as possible. Additionally, here are

some practical considerations below to keep yourself as informed and safe as possible:

Consider whether you should carry ID on your person:

Depending on your specific situation, it may be a good idea to carry ID when you leave your home.

However, if you currently have a warrant for your arrest, ID will generally not help you reduce the risk

of arrest and detention. For those with status or at least without a warrant outstanding, not having

identification may lead to a situation where you attract further investigation from law enforcement and

potentially a fine or imprisonment (particularly if you are driving or riding a bike). You may want to

52

‘Practical tips’ do not constitute legal advice; see Section 1.1 “Disclaimer” for more information.

51

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 40.

50

This can include people who just helped to smuggle others into Canada, such as if you assisted with crewing a boat that is

bringing refugees to Canada.

49

Ibid at s 37.

48

Ibid at s 36(1).

47

Ibid at s 35(1).

16

leave your ID (or copy of your ID) with someone you trust who you can contact if you are arrested or

put it somewhere safe and let someone know where that important documentation is.

Protection of personal information:

There are certain things you can do to protect your personal information. You have the right to ask

exactly what information you need to disclose, why the information is needed, how the information will

be used, and if it will be shared with others.

53

Typically, identifying information includes your name,

date of birth, and address. You can refrain from sharing any further information than what is needed.

54

If you work for a service provider or organization, you must obtain prior and informed consent before

sharing the personal information of the individuals that you support; your organization should also

explain the risks and potential consequences to individuals of sharing their personal information before

they do so.

55

You should not apply your own assumptions to a person’s situation but see it from their

viewpoint and respect their agency. Service providers should not police clients, but support and inform

them.

Truthfulness:

Based on IRPA, a person who has made an application for immigration status must answer all

questions truthfully

56

, including on any immigration application.

57

This has been interpreted to include

when a person has been arrested or detained and is ‘applying’ to be released.

57

Ibid at s 16(1).

56

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 16(1).

55

Ibid at 13, 23.

54

Butterfly, “Pathway to End Violence”, supra note 42 at 13, 23.

53

See IRPA, supra note 2 at s 16; Butterfly, “Pathway to End Violence”, supra note 42 at 13, 23.

17

3. HOW WILL I KNOW IF I AM

FACING DEPORTATION AND HOW

CAN I REGULARIZE STATUS?

3.1 How to check status

58

You are able to check your immigration/

refugee status online, including your place in

any of your immigration/refugee applications,

through Canada’s IRCC website.

59

If you do

not have an online account, you may create

one through the website. Checking online on

the IRCC portal

60

is usually more effective

than calling immigration’s number

(1-888-242- 2100).

61

Using the portal, IRCC

will forward the question to the appropriate

office, while the clerks at the call line only

have access to what is on your computer file

(which is relatively minimal).

62

To check the status of your

immigration/refugee application(s):

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-r

efugees-citizenship/services/application/

check-status.html

Alternatively, you can check the standard

processing times for your specific

application type here:

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-r

efugees-citizenship/services/application/

check-processing-times.html

Existing Immigration/Refugee Status:

You can see on the IRCC website after logging into your account whether you have existing

documentation proving your immigration status (rather than starting a new application).

63

This could

include copies of your existing work permit or study permit, proof that you are a permanent resident or

refugee claimant, or proof that you have a particular visa (e.g. a visitor visa).

64

You can also make

64

Ibid.

63

Steps to Justice, “Immigration Status”, supra note 57.

62

Ibid.

61

Government of Canada, “Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Client Support Centre services” (8 May 2020),

online: <www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/contact-ircc/client-support-centre.html>

[perma.cc/P8M2-JPXF].

60

Government of Canada, “IRCC Webform” (Date modified: 14 November 2018), online:

<secure.cic.gc.ca/enquiries-renseignements/canada-case-cas-eng.aspx?_ga=2.179401956.1591196388.1522176277-5541

00599.1522176277> [perma.cc/6MWL-D8SU].

59

Government of Canada, “Immigration and Citizenship” (Date modified: 19 March 2020), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/en/services/immigration-citizenship.html> [perma.cc/SMH7-QDVN].

58

Steps to Justice, “2. Find out your immigration status” (accessed 30 March 2020), online:

<https://stepstojustice.ca/steps/family-law/2-find-out-your-immigration-status> [perma.cc/Y7S7-PPF2] [Steps to Justice,

“Immigration Status”].

18

applications for temporary or permanent resident status either online or through the mail, including

extensions of temporary status and work and study visas.

Application Status:

Once processing of your specific application has begun, you will often be able to view the status of

your application.

65

Alternatively, if you are not able to check your application status (e.g. checking

online is unavailable for your specific application), you can view the standard processing times for your

application type to estimate the time it will take to have your application assessed.

66

Access to Information and Privacy Act Requests (ATIPs):

For more detailed information, you may file an ATIP request with the relevant government of Canada

department.

67

For example, if you wish to get the full file and notes on your immigration status and

related applications and interviews, you can file an ATIP with IRCC. There may be a significant time

delay between your request and the government’s response (usually at least several months). ATIPs

actually refer to information requests made under two separate acts. They give you access to

government records for departments under the act and cost $5.

Privacy Act requests can only be made by individuals in Canada for personal information held by

government institutions. They do not have a fee.

3.2 What is a Removal Order?

68

If you receive a Removal Order, it means that you cannot legally remain in Canada and must leave the

country. Depending on your situation, your removal order may be effective immediately, or after a

negative decision if you had made an appeal.

There are three types of Removal Orders which are issued by either the CBSA or IRCC. These are

(from most minor to most severe): Departure Orders, Exclusion Orders, and Deportation Orders.

68

IRPR, supra note 2 at ss 223-226; See Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “ENF 10

Removals” (24 February 2017), online:

<www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf10-eng.pdf>

[https://perma.cc/2SM5-GH65] [Operation Manual, “ENF 10”]; Canada Border Services Agency, “Arrests, detentions and

removals: Removal from Canada” (Date modified: 2020-02-03), online:

<www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/security-securite/rem-ren-eng.html> [https://perma.cc/4445-7252].

67

You may file an ATIP online at <https://atip-aiprp.apps.gc.ca/atip/welcome.do>.

66

Government of Canada, “Check processing times” (Date modified: 24 March 2020), online:

<www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/application/check-processing-times.html>

[https://perma.cc/6EPF-PQVH].

65

Government of Canada, “Check your application status” (Date modified: 23 March 2020), online:

<www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/application/check-status.html> [https://perma.cc/UE9Y-3KQJ]

[“Check your application status”].

19

Departure Order

With a Departure Order, you will be ordered to leave Canada within 30 days after the order takes

effect. You must also confirm your departure with the CBSA at your port of exit. If you leave Canada

and follow these procedures, you may return to Canada in the future provided you meet the entry

requirements at that time.

If you leave Canada after 30 days or do not confirm your departure with the CBSA, your Departure

Order will automatically become a Deportation Order. In order to return to Canada in the future, you

must obtain an Authorization to Return to Canada (“ARC”).

69

Exclusion Order

With an Exclusion Order, you will be ordered to leave Canada and cannot return to Canada for one

year. If you wish to return within a year, you must apply for an ARC. If an exclusion order has been

issued for misrepresentation, you cannot return to Canada for five years. If the CBSA paid for your

removal from Canada, you will be obligated to repay that cost to be eligible to return.

70

Deportation Order

If you are issued a Deportation Order, you will no longer be legally allowed to remain in the country. It

means that you will be forced to leave whether you pay for a way to leave on your own, or

alternatively you are arrested, detained, and subsequently deported from Canada by the government

themselves. A Deportation Order is the most severe of the three removal orders, as you will be

permanently barred from returning to Canada and cannot return unless you apply for an ARC. If the

CBSA paid for your removal from Canada, you must also repay that cost before you are eligible to

return.

71

There will be a ‘form number’ on your removal order which will indicate if it is a deportation order,

departure order, or exclusion order. Be sure to double check what kind of removal order you have to

assess what steps to take.

3.3 How to regularize or retain status

There are various ways to regularize or retain immigration or refugee status in Canada. Regularizing

status refers to actions taken to legalize an individual’s status within a country. While each person’s

immigration situation is unique and should be discussed with a qualified immigration lawyer or

consultant, the following outlines some common tips and methods.

71

Ibid at s 49.4.

70

Operation Manual, “ENF 10”, supra note 68 at s 49.2.

69

For more information on the ‘Authorization to Return to Canada’ process, see Government of Canada, “Authorization to

return to Canada”, supra note 25 (Date modified: 27 March 2020), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/inadmissibility/reasons/authorization

-return-canada.html> [https://perma.cc/6QFD-ULY6].

20

Ensuring that you follow all steps/requirements to keep/renew your status:

72

It is generally easier retaining status than regularizing when you are out of status. Therefore, you

should make all efforts to follow the necessary steps needed to follow the conditions of your particular

status and to preserve the possibility of renewing it in the future. For instance, if a work permit is

‘closed’ in that it only allows you to work for one particular employer, working with a different

employer could result in the invalidation of your work permit.

73

You should pay careful attention to the

specific requirements of your particular visa as well as the steps you will need to take if you wish to

renew it in the future. If you are planning to renew, apply early.

Visitor Visas (Extension):

74

If you already have a visitor visa, you can extend your

status as a visitor through applying for a ‘Visitor Record’.

A ‘Visitor Record’ is not a new visitor visa; it will instead

extend your ability to stay in Canada as a visitor and

create a new expiration date for your visitor visa. You

will need to apply for it before your current visitor visa’s

expiration date; as stated in Section 2.1, visitor visas are

generally 6 months in length.

75

The government

recommends individuals to apply 30 days prior to the

visa’s expiration date. The processing time is about 100

days if you apply online.

76

The application fee is $100.

To apply for a ‘Visitor

Record’ to extend the

expiration date of your

visitor visa, you can go to:

https://www.canada.ca/en/immi

gration-refugees-citizenship/ser

vices/application/account.html

If you apply before the expiration date, you will be granted “implied status” – meaning that you will

have status until a decision is made on your extension application. The success of your application

could depend on many factors, such as if you can demonstrate that you have the ability to financially

support yourself (including money earned without a valid work permit).

Refugee and Protected Persons Claims:

77

You can claim refugee status if you are 1) outside the country that you are from/habitually live in 2)

have a “well-founded fear of persecution” in that country due to your race, religion, political actions,

nationality, or membership in a particular social group and 3) you are unable or unwilling to receive

77

Ideas for this section were developed through consultation with migrant communities in Toronto in August 2019.

76

You can start an application to extend your visitor status by visiting:

<www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/application/account.html>.

75

See Government of Canada, “Visitor visa: About the document” (Date modified: 20 March 2020), online:

<www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/visit-canada/about-visitor-visa.html>

[https://perma.cc/EET7-5PZG].

74

See Government of Canada, “Extend your stay in Canada” (Date modified: 23 March 2020), online:

<www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/visit-canada/extend-stay.html>.

73

Butterfly, “Upholding and promoting human rights- Part 1”, supra note 29 at 25.

72

Ideas for this section were developed through consultation with migrant communities in Toronto in August, 2019.

21

help from that country (i.e. they are unable/unwilling to protect you from this persecution) due to your

fear.

78

Additionally, you can still qualify as a refugee even if you did not originally leave your home country

due to some fear. If you instead developed a ‘well-founded fear of persecution’ while away from your

home country and have that fear right now, you can make a claim known as a sur place claim. You

cannot make a refugee claim if you are under an active removal order.

79

You may apply as a person in need of protection if you face danger of torture, risk to your life, or risk of

cruel and unusual treatment or punishment if you return to your home country.

If you are not sure whether you qualify as a refugee or a person in need of protection or would like

further legal advice, you can consult Section 6 of this guide.

If you think you may qualify as a refugee or protected person in Canada, you can

start your claim at an Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) oce or

at an authorized port of entry to Canada. You must also complete all of the forms

from the application package, which you can access at:

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/application/application-form

s-guides/applying-refugee-protection-canada.html

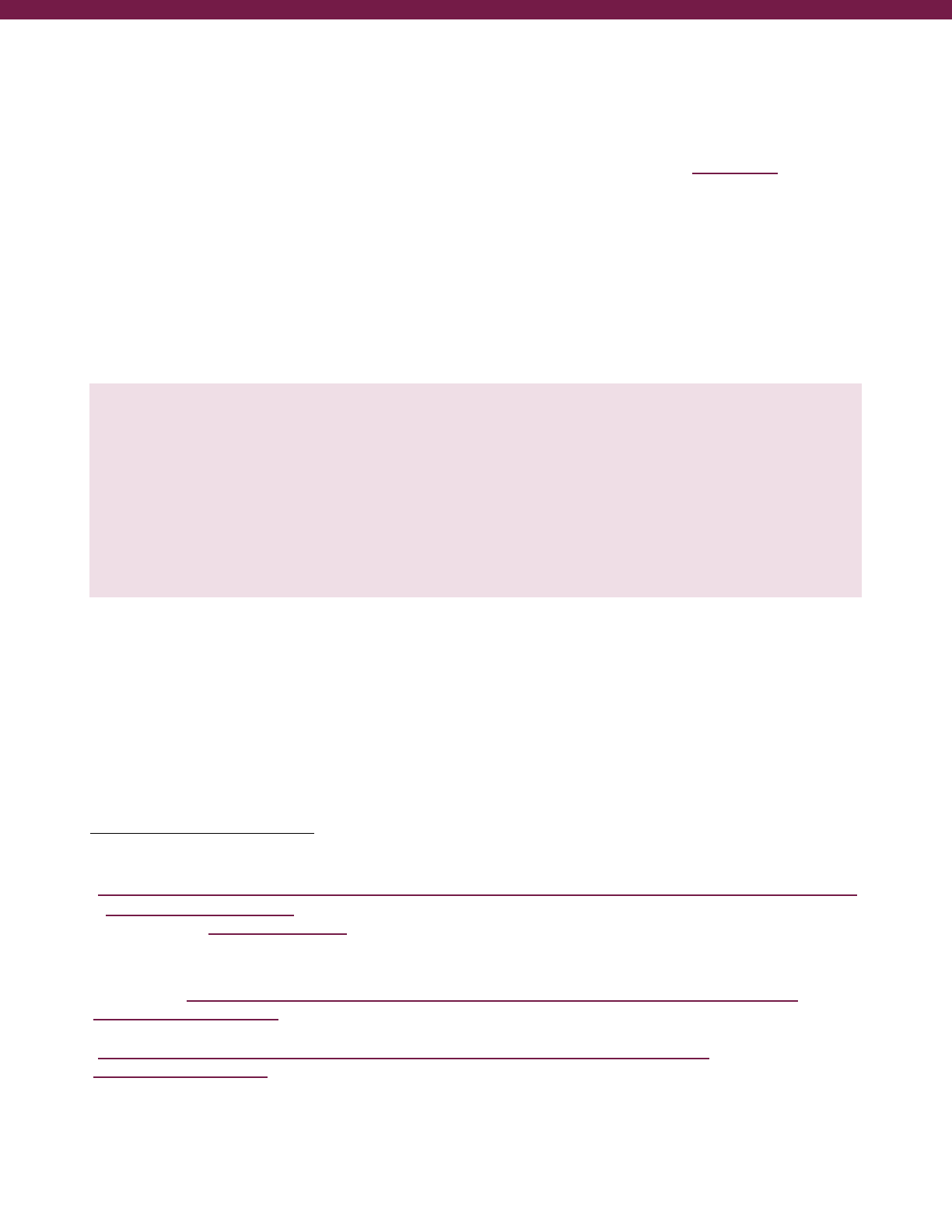

Humanitarian and Compassionate Grounds:

In exceptional situations, if you would not

otherwise qualify for immigration/refugee status,

you could apply to be granted permanent resident

status by IRCC on ‘Humanitarian and

Compassionate grounds’ (“H&C”).

In assessing your application, IRCC may consider

many different factors, including whether you will

face hardship or other harmful consequences in

your home country if you were forced to leave

Canada, if you are settled in Canada (such as

through having financial or family ties), and the

effect of your removal from Canada on any

involved children’s best interests. Showing that

you can support yourself financially without social

assistance is an important factor in an H&C

application. To that end, being gainfully employed

or running a business could be a positive factor.

An H&C looks broadly at many

different factors to assess the

case:

● Ties and establishment to

Canada

● Best interests of children

affected

● Host country conditions

● Health

● Family, including violence and

consequences of family

separation

● Other exceptional circumstances

79

Ibid at s 99(3).

78

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 96.

22

You cannot have a refugee claim that is still pending when applying for H&C. Before applying, you

should consult the IRCC’s application package and a qualified immigration lawyer or consultant.

80

Spousal Sponsorship:

81

You may be eligible to apply for immigration status if you are the spouse, common-law partner, or

conjugal partner of a Canadian citizen or permanent resident as they could apply to sponsor you in

becoming a permanent resident; this includes same-sex partnerships as well. Any prospective spousal

sponsor would need to be able to support you financially and ensure that you will not need

government social assistance while living as a permanent resident. It takes approximately a year for

IRCC to process the application.

It is important to prepare documentation and answer questions together with your spouse. The IRPA

does not allow for relationships that are not genuine or entered into for the primary purpose of

acquiring status.

82

Immigration officials are therefore very sensitive to indicators of a bad faith

application and inconsistencies between spouses and family/friends regarding dates and details.

Having children can be a large factor in the success of your application, and whether your spousal

relationship is deemed as ‘legitimate’ or not by the IRCC. ‘Dependent children’ can also be sponsored

for permanent resident status; the application fee is around $150, and the processing times will vary

from country to country.

83

Further information on eligibility requirements and the application process for

spousal sponsorship can be found on:

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/family-sp

onsorship/spouse-partner-children.html

83

Government of Canada, “Sponsor your spouse, partner or child” (Date modified: 13 November 2019), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/family-sponsorship/spouse-partner-

children.html>.

82

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 4(1).

81

Government of Canada, “Sponsor your spouse, partner or child” (Date modified: 13 November 2019), online:

<www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/family-sponsorship/spouse-partner-childre

n.html>.

80

You can access the IRCC’s application package online at:

www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/application/application-forms-guides/humanitarian-compassion

ate-considerations.html.

23

4. WHAT IS THE DEPORTATION

PROCESS AND WHAT SHOULD I DO

IF I AM BEING DEPORTED?

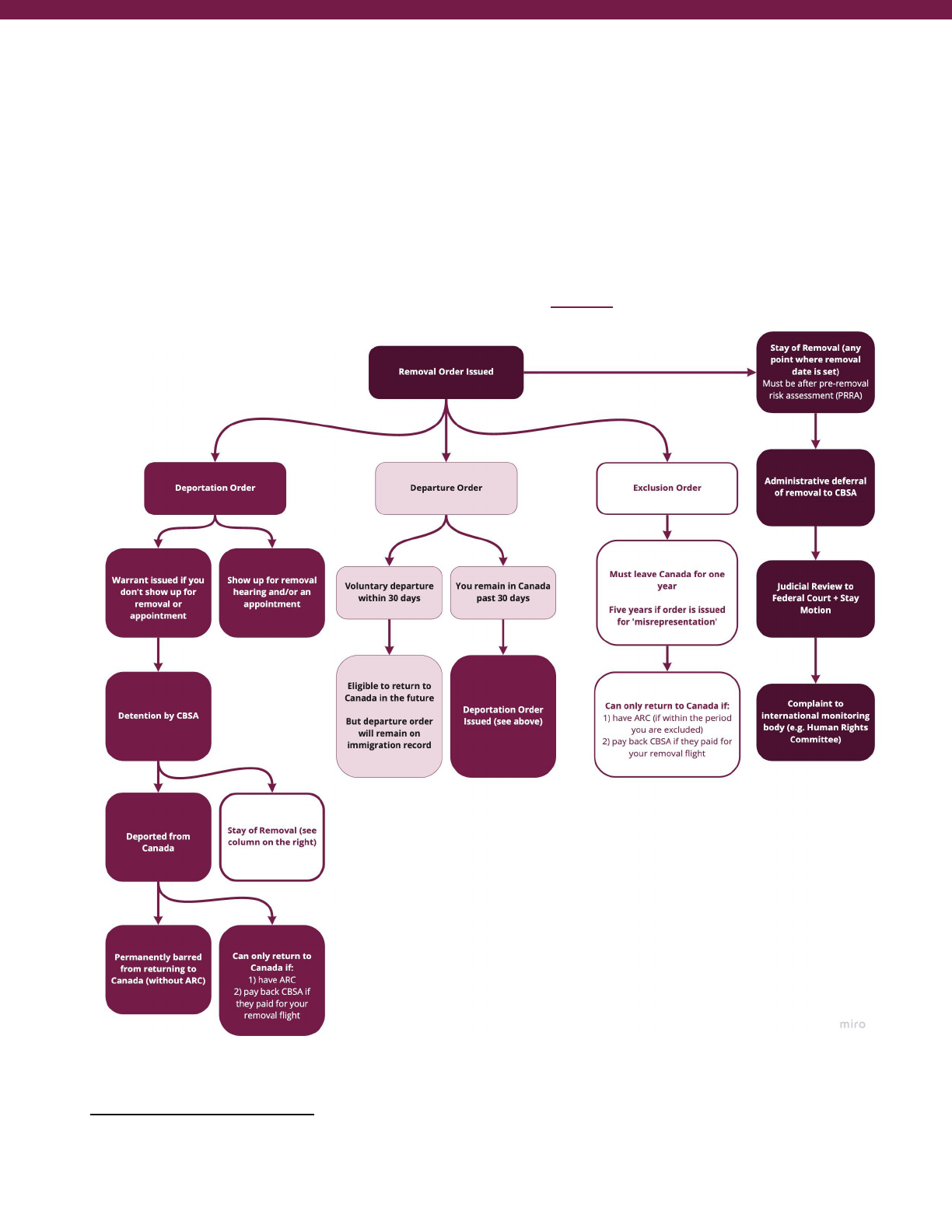

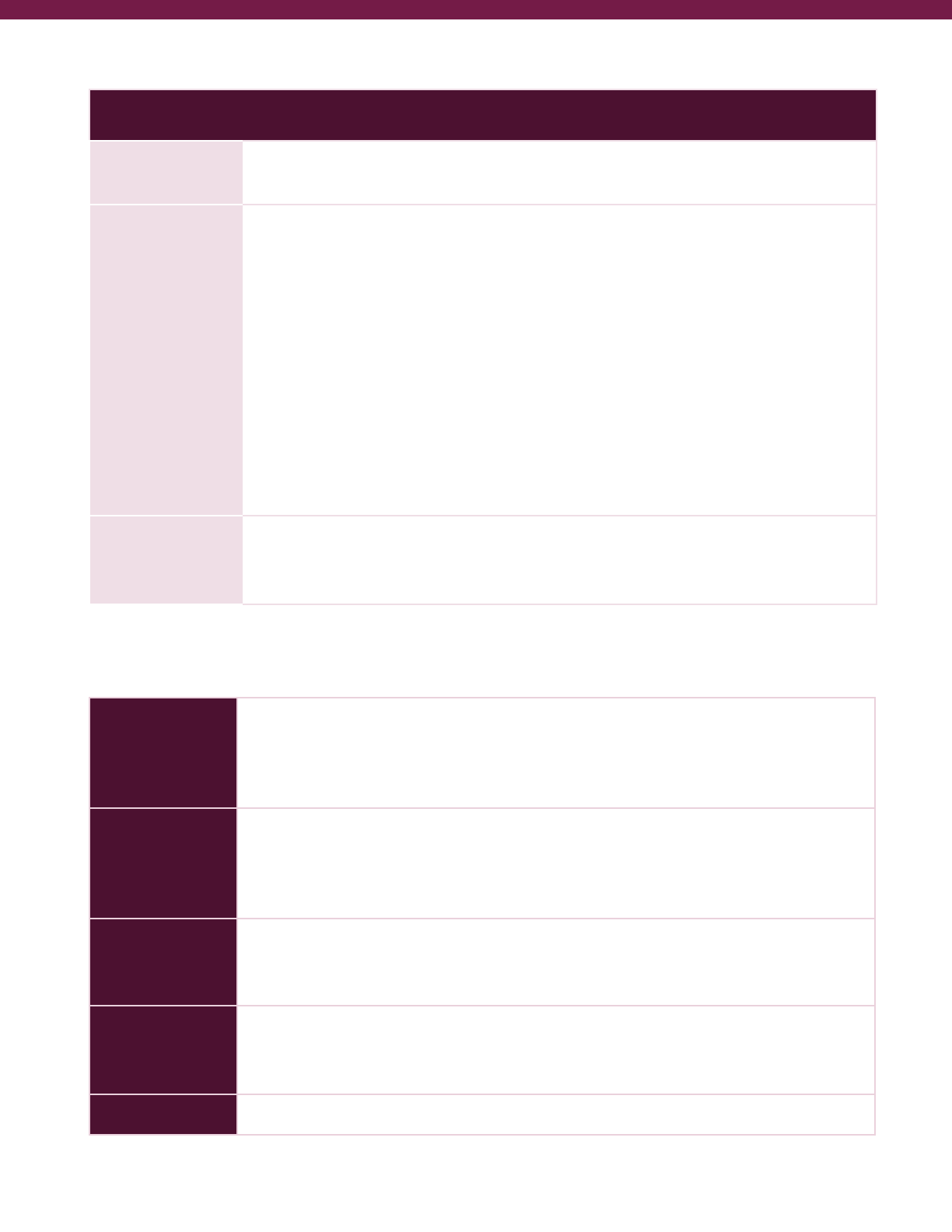

4.1 Deportation process flowchart

84

*Note: This flowchart does not include avenues to regularize or extend status (e.g. visa renewals, refugee/protected person claims, H&C,

family sponsorship), which can generally be initiated at any point in the process. See Section 3.3 of this guide for more detailed treatment:

84

This flowchart was informed/developed by relying on Operation Manual, “ENF 10”, supra note 68.

24

4.2 Safety plan in case of arrest

85

It is important to have a safety plan in case you are arrested. If you are not prepared and do not have a

plan, it could be extremely difficult for you to manage your affairs and have support during/after your

arrest.

Assign someone that you trust and rely on to provide you with support in the event that you are

arrested. You could give this person a key to your house so that they could look after your pets, kids,

plants, or manage any other necessary household tasks, or retrieve important documents for your case

if your arrest leads to detention (or provide a way for accessing this information through a secure

online method).

86

Given that this is someone who you trust, you could also tell them your immigration

status beforehand so that they know of the risks you face and the support that you may need from

them.

87

Ideally, this person should be a permanent resident or Canadian citizen, able to attend your

bail/detention review hearing and post your bond, and someone who you could live with if you post

bond.

88

They may ask both of you a lot of questions to prove you have a genuine relationship.

If this is not possible, consider reaching out to

migrant-friendly support organizations that could provide

support and contact your loved ones in case you are

arrested and detained. Having a strong support network

that can keep in touch with you and rally together to get

you out of detention is beneficial and empowering for all.

You should also do what is necessary to prepare on your

own. Memorize the names and numbers of contacts that

are important to you in case you do not have access to your

belongings while arrested; this could include a trustworthy

‘representative’ (see above), family members, friends, an

immigration lawyer or consultant, members of community

and faith organizations, and so on.

Most importantly, make sure that you know your rights

yourself in the event that someone tries to arrest you.

Know your current status and the specific risk of

immigration arrest and detention.

88

Ibid.

87

Ibid.

86

Advice on this component of potential safety plans was developed through consultation with migrant communities in

Toronto in September, 2019.

85

Butterfly, “Who is who”, supra note 27 at 9.

25

4.3 Reporting to CBSA

You may or may not need to report to the CBSA in order to comply with Canadian immigration law,

such as to meet the requirements of your particular visa or the conditions of your ‘alternative to

detention’ arrangement.

89

In some cases, particularly for persons still awaiting immigration

applications, with expired status, or otherwise precarious status, CBSA may require you to periodically

report to them. As stated in Section 1.5, it is important to remember that CBSA officers have the power

to arrest and detain individuals who violate immigration laws, but do not have the power to enforce

criminal laws.

How to respond if CBSA requests new information from you:

90

The CBSA may require you to report changes to personal information (e.g. a change in address) or

request your presence at particular locations (e.g. the airport). In general, any immigration

‘investigation’ should not be arbitrary; there needs to be a reasonable basis for the CBSA officer to

conduct any particular investigation.

CBSA may require you to provide your new address before you move (in writing); this means you need

to go to a local CBSA office, fill out a form and show your new address before you move.

91

In addition,

the CBSA Immigration Processing Centre (IPC) may request additional information from you in the

form of a letter if they need more information to determine your admissibility to Canada and/or make a

decision with regard to your immigration status; you would need to respond to the CBSA within 30

days of the letter’s issuance.

92

Phone reporting:

93

In certain situations, individuals with precarious status will be required to report periodically (usually

monthly) to the CBSA by phone. This procedure used to involve reaching a live agent, but now is

largely facilitated by voice recognition software.

94

Failure to report by phone may result in

consequences, such as the initiation of removal proceedings by the Minister or the issuance of an arrest

warrant. Speak carefully and clearly as everything that you say will be put on record. If you call using a

cell phone, your GPS location may be recorded.

94

Immigration.ca, “CBSA Turning to Voice Recognition to Help Limit Immigration Detention” (17 January 2018), online:

<https://www.immigration.ca/cbsa-turning-voice-recognition-help-limit-immigration-detention>.

93

Operation Manual, “ENF 34”, supra note 89 at 5.

92

See Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “ENF 29 Alternative Means of Examination

Programs” (17 June 2005), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf29-eng.pdf> at 10, 20.

91

First-hand experience with the CBSA in this regard was provided during consultations with migrant communities in Toronto

in January 2020.

90

See Operation Manual, “ENF 10”, supra note 68; “ENF 7”, supra note 30 at 34, 38, 39.

89

See Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “ENF 34 Alternatives to Detention Program”

(22 June 2018), online: <https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf34-eng.pdf>

at 5 [Operation Manual, “ENF 34”].

26

In-person reporting:

95

When you are reporting to the CBSA in person with regard to voluntary removal from Canada or to

meet other CBSA-imposed conditions, you should consider the following:

● Make sure you go with somebody (whether it be a friend, family member, interpreter, legal

representative, or other form of support);

● Ask for an interpreter, if necessary;

● Always say you will meet and follow their conditions, and show up to any scheduled

appointments/sessions (they will record your attendance in their system);

● Avoid discussing your fear or reluctance in returning to your home country during these

reporting sessions, as it may increase the risk of being detained as a flight risk;

● Have the relevant documentation ready;

● Inform them if you change your address or phone number;

● If you are asked to sign a document and are not sure about it, insist that you bring it back to

your lawyer to speak about it first.

Search and seizure:

96

Under IRPA, immigration officials have the power to search you and seize your belongings if they

believe (on reasonable grounds) that your belongings were obtained or are being used

fraudulently/improperly, or if conducting the search and/or seizing the belongings will ensure

compliance with IRPA and its objectives. The CBSA has, in effect, broad discretion to seize your

belongings when they see fit, so long as it is ‘reasonable’ to do so. In that light, they may have the

authority to seize your phone or your other belongings when you are reporting to the CBSA. If you feel

your documents or belongings have been removed in an unlawful way, contact counsel.

96

Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “ENF 12 Search, Seizure, Fingerprinting and

Photographing” (25 October 2018), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf12-eng.pdf> at 6; IRPA, supra note

2 at s 140.

95

See Operation Manual, “ENF 34”, supra note 89 at 5.

27

4.4 Practical tips

You can follow some practical tips below in order to better understand and navigate the deportation

process, as well as to minimize your risk of immigration arrest and detention:

97

Law enforcement at your home:

98

If an officer comes to your front door at home, how can you respond? First, you may want to see if they

are wearing a uniform or are a plainclothes officer. Next, you may want to know what kind of officer

they are to determine their powers.

You have privacy rights and may refuse entry, unless they have the necessary warrants. You can first

determine whether they do in fact have the necessary warrants by asking them if they 1) have an

immigration arrest warrant and 2) have a warrant that allows them to enter your home (known as both

a ‘Feeney Warrant’ or a ‘Special Entry Warrant’).

If they do not have both of these warrants, or there are mistakes on the warrants, your name is not on

the warrants, or there is some other issue with either warrant, they are not legally allowed to enter

your home and you have the right to refuse them entry (i.e. politely ask them to leave). When asking

them for these warrants, it is also important that you do not open your door as they may force

themselves in if you give them the chance. You can instead request for the warrants to be put in a

mailbox or slipped under your door; if that is not possible, then you could slightly open the door to

receive the warrants. Be aware that although this is totally within your rights, if you are detained by

immigration it may be used as evidence that you were not cooperative and may be a flight risk.

Phone passwords:

Make sure to put a password on your phone to protect your privacy; this could prevent officers from

reading your text messages, seeing sensitive photos, or other information on your phone that could

negatively affect your immigration/refugee status.

99

This may be particularly important to avoid law

enforcement targeting others and for those working in the sex industry.

Prolonged detention:

If you are detained or arrested by the CBSA, they can hold you if they are not sure of your identity or

you don’t have citizenship or permanent residency

100

. This means you have to make a decision: do you

answer their questions and hope they release you, or do you remain silent? You have the right to

counsel under section 10(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, so if you can access a

lawyer or counsel, you should talk to them before answering questions.

100

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 55(2)(b).

99

This practical tip was provided during consultations with migrant communities in Toronto in August, 2019.

98

Immigration Legal Committee, “Migrants Know Your Rights!” supra note 1 at 4.

97

These ‘practical tips’ do not constitute legal advice; see Section 1.1 “Disclaimer” for more information.

28

5. WHAT IF I AM ARRESTED AND

PUT IN IMMIGRATION DETENTION?

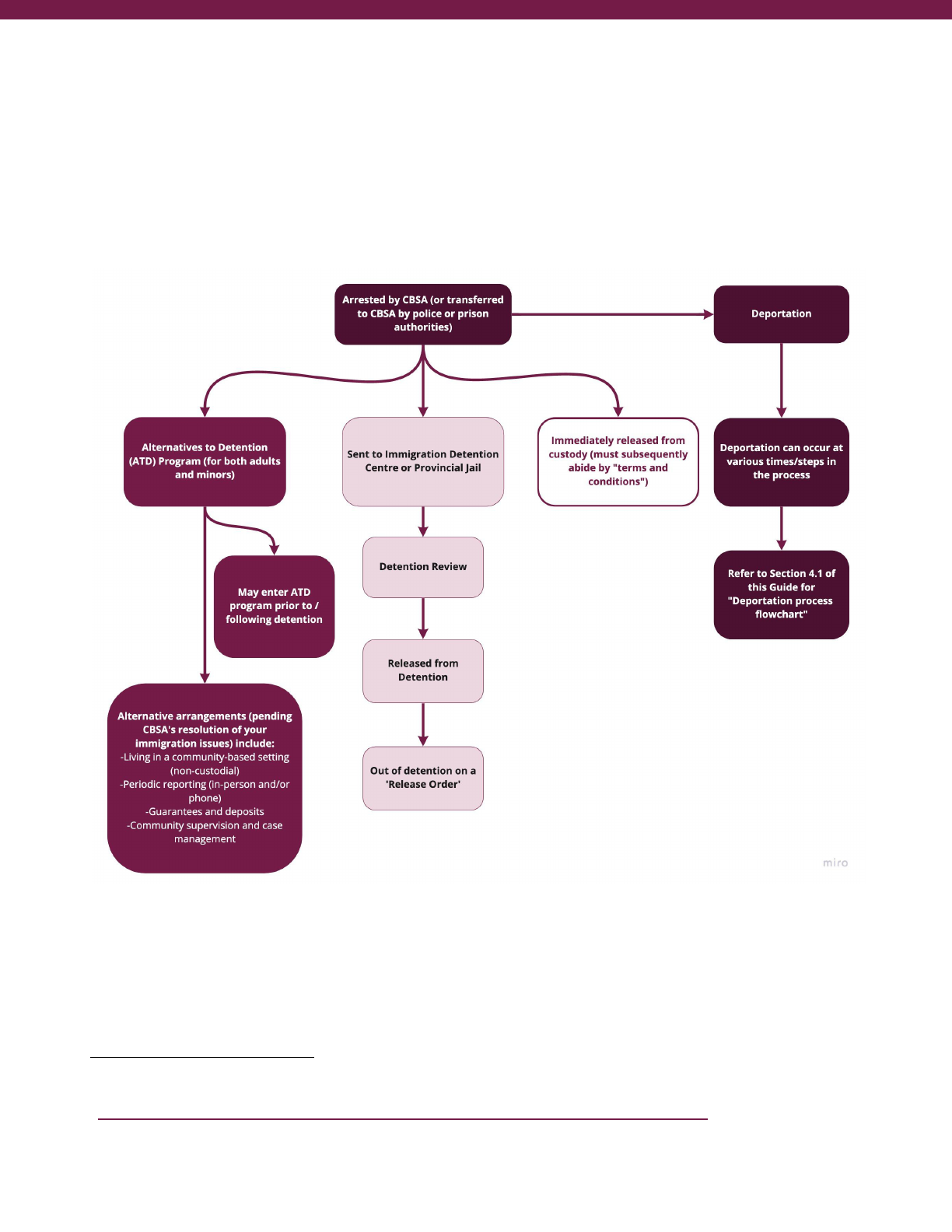

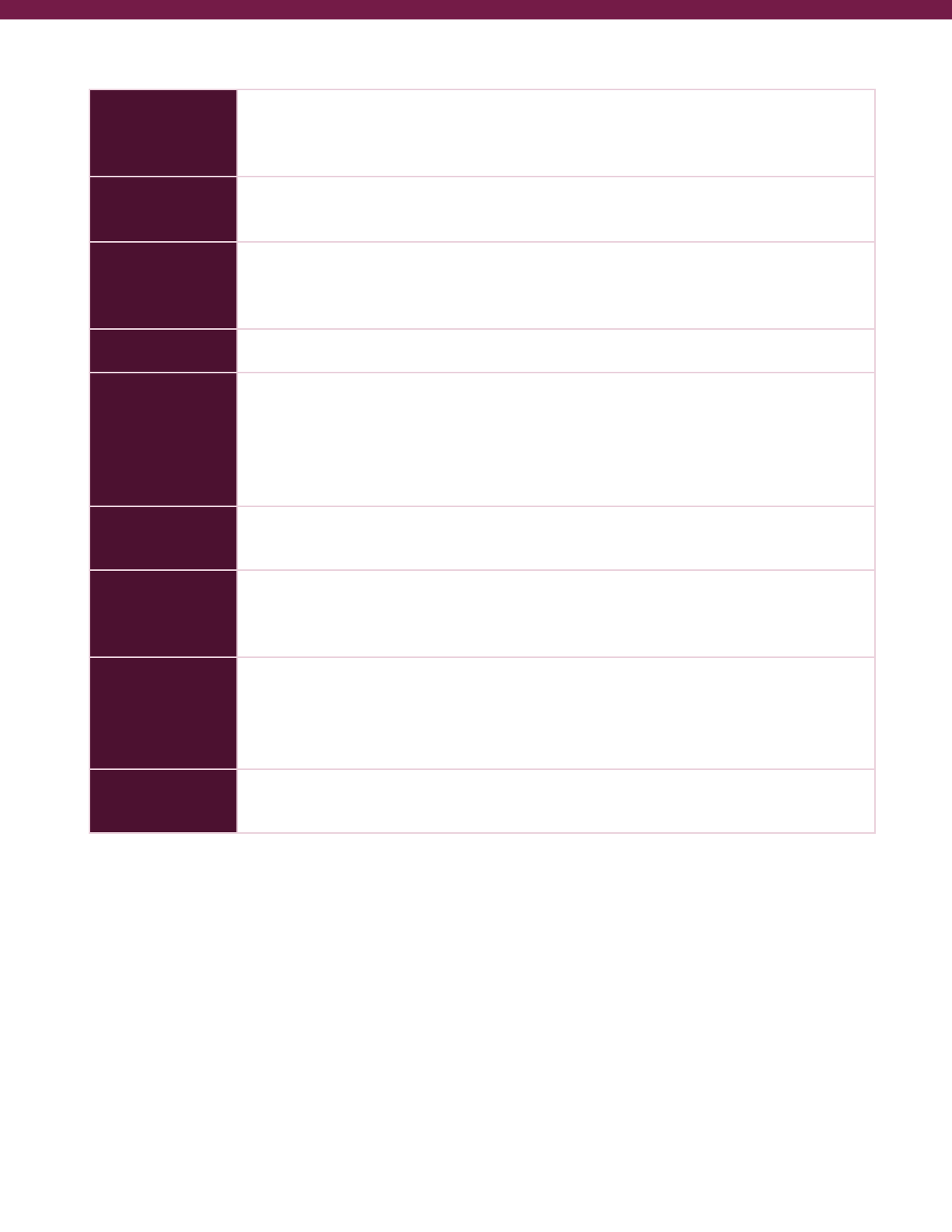

5.1 Detention process flowchart

101

101

This flowchart was informed by the following sources: Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

(IRCC), “ENF 20 Detention” (Last Updated: 23 March 2020), online:

<https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf20a-en.pdf> [Operation Manual,

“ENF 20”]; IRPR, supra note 2 at s 248; Operation Manual, “ENF 34”, supra note 89.

29

5.2 Grounds for immigration detention

It is important that you know the grounds for immigration detention in order to avoid giving CBSA any

impression that you should be detained. Under IRPA, along with guidance from IRPR, the CBSA has

grounds to detain you if they have a reasonable belief that:

102

You are inadmissible and otherwise do not have valid status:

See Chapter 2 of this guide for discussion surrounding inadmissibility and common ways that

individuals fall out of status.

You are deemed a flight risk – unlikely to present yourself for examinations, inadmissibility

hearings, or hearings related to removal orders:

Determining factors from IRPR include: being a fugitive of justice, whether or not you complied with

previous removal orders or in immigration/criminal proceedings (even if the notice was not received),

you tried to escape from custody previously, you are strongly connected to an organization based in

Canada, or you were involved with organizations that engage in human smuggling/trafficking.

You are deemed a danger to the Canadian public:

Determining factors from IRPR include: if you were convicted in Canada for sexual and/or violent

offences, trafficking and other drug trade related offences, or you had convictions in other countries for

similar crimes. These determinations can often be animated by stereotypes regarding race and

criminality and perpetuate systemic racism in criminal justice systems more broadly and policing and

convictions specifically.

103

Your identity is in question in any of your immigration proceedings under IRPA:

Determining factors from IRPR include: if you cooperate in providing the CBSA with detailed evidence

on your identification, family history, and travel plans/history to Canada; if you destroyed your

identification documents, used fraudulent documentation in your interactions with the CBSA,

104

and/or

provided documents which were inconsistent/contradictory with one another. If you have used a

different identity or fraudulent identity documents, you should speak with counsel to discuss your

options.

104

See Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Singh, 2004 FC 1634 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/1j9h5> at para 3.

103

See Robyn Maynard, “Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present” (2017 Fernwood

Publishing).

102

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 55; IRPR, supra note 2 at R 244 – 250.

30

5.3 Rights when you are arrested and detained

Under Canadian law, you have certain rights when you are arrested and detained. You may exercise

these various rights if you so choose, including the following:

Right to speak to counsel:

105

As stated above, you have the right to counsel

per section 10(b) of the Canadian Charter of

Rights and Freedoms; you have the right to

speak to a lawyer/legal counsel before

answering any questions while arrested. This

applies for both police and CBSA arrests. If you

cannot afford private legal counsel, you may be

eligible for your province or territory’s legal aid

organization. See Section 6.1 – Legal Aid.

You can exercise your rights when

you are arrested and detained —

you have the right to:

● Speak to counsel

● Remain silent

● Contact your home country’s

consulate

● Detention reviews

● A phone call

Right to remain silent:

106

If you are arrested by the CBSA, you have the right to contact a lawyer/counsel before answering any

questions. Similarly, if you are arrested by the police you have the right to remain silent. Once you are

in immigration detention, however, your silence and refusal to answer questions posed by the

authorities could factor into your detention review and delay your release (see Section 5.4 “What to

Expect in Detention” for more information on detention reviews).

Right to contact your home country’s consulate:

107

You also have the right to contact the consulate of your home country. Depending on the country, they

may be able to support or assist you in some way. However, in certain cases contacting your home

country’s consulate may not always be advisable. Some consulates may be more interested in

maintaining/developing their relationship with Canadian authorities and facilitating deportation than

providing assistance.

108

It is also not advisable to contact your home country’s consulate if you are an

asylum seeker and fear persecution from your home country.

108

This opinion was provided during consultations with migrant communities in Toronto in January, 2020.

107

See Canada Border Services Agency, “Arrests, detentions and removals” (Date modified: 24 July 2018), online:

<www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/security-securite/arr-det-eng.html> [https://perma.cc/4445-7252].

106

Stella/Butterfly’s “Immigration Status And Sex Work” Guide (Published March 2015) at 20; Butterfly, “Upholding and

promoting human rights- Part 1”, supra note 29 at 19.

105

Ideas for this section were developed through consultation with migrant communities in Toronto in September, 2019.

31

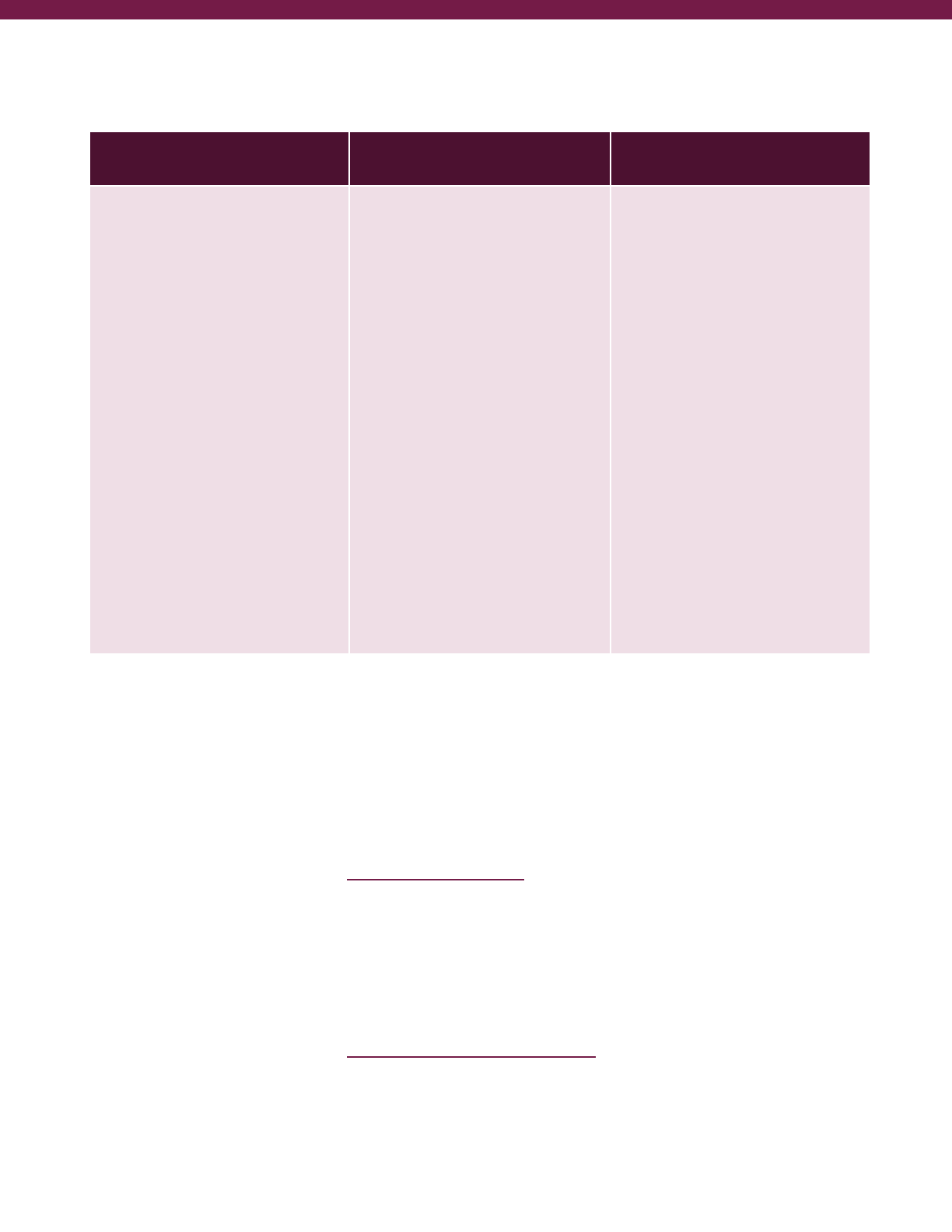

Right to a detention review:

109

If you are detained, you will have the right (and be legally required) to have various detention reviews.

In these reviews, the IRB will consider whether your detention is lawful and/or whether you should be

released. You also have the right to be represented by counsel in detention review hearings. You will

have an initial detention review within 48 hours of your detention. Following that review, you will have

another detention review in 7 days, and then subsequently get reviews every 30 days (see Section 5.4

“What to Expect in Detention” for more information on detention reviews).

Phone call rights:

110

You should be given a phone call to contact your counsel and/or another emergency contact if you are

arrested.

111

If you are refused one, demand your right to call someone. You have the right to make as

many phone calls as needed to find counsel. As stated above in Section 4.2 (“Safety Plan in Case of

Arrest”), memorizing the numbers of important contacts (e.g. lawyers, community workers, close

friends and family) could prove to be useful, especially if your cell phone is taken away from you.

5.4 What to expect in detention

Conditions in immigration detention may vary depending on which facility you are detained in, the

specific officers in charge of your detention, and many other factors. Although experiences in detention

will be highly individualized and context-specific, there are certain facts/risks that will be fairly

consistent for every immigration detainee. You can expect the following when you are in detention:

Specific detention centers:

112

You may be sent to either a provincial jail or a CBSA Immigration Holding Centre. While detained, you

may also be relocated to another facility. But regardless of where you are being held, you will have a

detention review hearing within 48 hours, then another within 7 days, and another for each 30-day

period afterwards.

113

113

IRPA, supra note 2 at s 57(1)-(2).

112

See Operation Manual, “ENF 20”, supra note 101 at 28, 29, 42.

111

See R. v. Pavel (1989), 74 C.R. (3d) 195 (Ont. C.A.) at 311, 312 for a discussion about how you are able to make multiple

calls in order to first speak to a lawyer.

110

See Canadian Civil Liberties Association, “Know Your Rights – A Citizen’s Guide to Rights When Dealing With Police”

(accessed 09 April 2020), online:

<www.peelpolice.ca/en/in-the-community/resources/Documents/Know-Your-Rights-Booklet.pdf> at 5, 6.

109

See Operation Manual - Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “ENF 3 Admissibility, Hearings and

Detention Review Proceedings” (29 April 2015), online:

<www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf03-eng.pdf> at 33-35; see also Operation

Manual, “ENF 20”, supra note 101 at 42; IRPA, supra note 2 at s 57; see Section 5.3 “What to Expect in Detention” for more

information on detention reviews.

32

If you are sent to a CBSA Immigration Holding Centre (as opposed to a provincial jail), you may be sent

to one of the following facilities:

114

Toronto Immigration Holding Centre

385 Rexdale Boulevard, Toronto, ON

(416) 401-8505

Vancouver Immigration Holding Centre

13130 76 Avenue, Surrey, BC

(778) 591-4101

Laval Immigration Holding Centre

200 Montée Saint-François, Laval, QC

(450) 661-4717

Alternatively, you may instead be sent to provincial jail (i.e. a normal jail for those who violate the

Canadian Criminal Code) if you are deemed to be a danger to the public. These jails are often mixed

with the general population as opposed to solely those who have violated immigration law. You will

also be sent to jail if you need medical assistance. Depending on your specific medical needs, however,

you may instead be sent to a mental health facility. Research shows that detainees are frequently not

notified in advance of the transfer, the reason for transfer, nor given a chance to meaningfully

challenge the decision.

115

Vanier Centre for Women

655 Martin St, Milton, ON

(905) 876-8300

Central East Correctional Centre

541 Kawartha Lakes County Rd 36, Lindsay, ON

(705) 328-6000

Toronto South Detention Centre

160 Horner Ave, Toronto, ON

(416) 354-4030

Fraser Regional Correctional Centre

13777 256 St, Maple Ridge, BC

(604) 462-9313

Montréal Bordeaux Prison